Difference between revisions of "Belshazzar"

m (1 revision imported) |

|

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 17:15, 30 March 2015

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Belshazzar (/bɛlˈʃæzər/; Biblical Hebrew בלשאצר; Akkadian: Bēl-šarra-uṣur) "Bel, protect the king", sometimes called Balthazar /ˈbælθəˌzɑr/, was a 6th-century BC prince of Babylon, the son of Nabonidus and the last king of Babylon, according to the Book of Daniel in the Hebrew Bible. In Daniel 5 and 8, Belshazzar is the King of Babylon before the advent of the Medes and Persians.[1]

Contents

Belshazzar in extra-Biblical sources

Belshazzar was the son of Nabonidus, the last king of Babylon, who frequently left him to govern the empire while he pursued antiquarian and religious interests. After ruling only three years, Nabonidus went to the oasis of Tayma and devoted himself to the worship of the moon god Sin. He made Belshazzar co-regent in 553 BC, leaving him in charge of Babylon's defense.[2] In his 17th year, 539 BC, Nabonidus returned from Tayma, hoping to defend his kingdom from the Persians who were planning to advance on Babylon. He celebrated the New Year's Festival (Akk. Akitu) in Babylon that year. Subsequently, Belshazzar was positioned in the city of Babylon to hold the capital, while Nabonidus marched his troops north to meet Cyrus. On October 10, 539 BC, Nabonidus surrendered and fled from Cyrus. Two days later, the Persian armies captured the city of Babylon.

Evidence that Belshazzar held the title of king, beyond the evidence given in the Book of Daniel, comes from a cuneiform tablet called “The Verse Account of Nabonidus,” where it is said that Nabonidus “entrusted the kingship” to his oldest son before leaving on his pilgrimage to Tema.[3] Also, in Xenophon’s Cyropaedia (4.6.3), Xenophon refers to a son of the Babylonian king whom he also calls a king, and this son/king was reigning in Babylon when Cyrus was preparing his army to advance against the city. Xenophon, without giving his name, also repeatedly refers to the "king" that was slain when Babylon fell to the army of Cyrus. Xenophon, in agreement with Herodotus (I.292), says that the combined Median and Persian army entered the city via the channel of the Euphrates River, the river having been diverted into trenches that Cyrus had dug for the purpose, and that the city was unprepared because of a great festival that was being observed.[4]

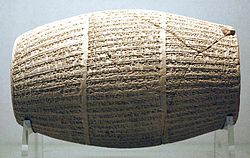

Xenophon relates that the leader of the forces that captured the city was Gobryas, governor of Gutium. This information, not found in Herodotus, was verified when the Cyrus Cylinder was translated, naming Gubaru as the leader of the forces that captured Babylon. Gubaru/Gobryas remarks that “this night the whole city is given over to revelry” (Cyropaedia 7.5.33). The capture of the city, and the slaying of its resident king, is described in the Cyropaedia (7:5.26-30) as follows:

(26) Thereupon they entered; and of those they met some were struck down and slain, and others fled into their houses, and some raised the hue and cry, but Gobryas and his friends covered the cry with their shouts, as though they were revellers themselves. And thus, making their way by the quickest route, they soon found themselves before the king’s palace. (27) Here the detachment under Gobryas and Gadatas found the gates closed, but the men appointed to attack the guards rushed on them as they lay drinking round a blazing fire, and closed with them then and there. (28) As the din grew louder and louder, those within became aware of the tumult, till, the king bidding them see what it meant, some of them opened the gates and ran out. (29) Gadatas and his men, seeing the gates swing wide, darted in, hard on the heels of the others who fled back again, and they chased them at the sword’s point into the presence of the king. (30) They found him on his feet, with his drawn scimitar in his hand. By sheer weight of numbers they overwhelmed him: and not one of his retinue escaped, they were all cut down, some flying, others snatching up anything to serve as a shield and defending themselves as best they could” .[5]

Curiously, the Book of Daniel offers no explanation of how the city could have been taken suddenly instead of after a long assault on its walls, or why King Belshazzar and his guests were so unaware of the danger that would lead to the loss of the kingdom, and of Belshazzar’s life, on the night of the famous banquet.

Belshazzar in the Book of Daniel

Although there is evidence in addition to the evidence supplied by the Bible that Belshazzar existed, his famous narrative and its details are only recorded in the Book of Daniel, which tells the story of Belshazzar seeing the writing on the wall. In Daniel Chapter 5, the details start off by there being a banquet for a thousand of his lords. Belshazzar next orders the vessels of gold that were taken from the Temple in Jerusalem, to be brought so that everyone can drink wine from them. It is at this moment that a man's hand appears and starts to write on a wall. Belshazzar's countenance is stated to have changed and he cries out to bring in his astrologers, Chaldeans and Soothsayers and that whoever interprets the writing will be made the third highest ruler in the kingdom. The queen comes in and suggests that he call for Daniel who is by now an old man because Nebuchadnezzar made him his chief of the Magicians, Astrologers, Chaldeans, and Soothsayers. Belshazzar offers Daniel the position of third highest ruler in the kingdom if he can interpret the writing but Daniel doesn't want to be rewarded. Daniel interprets the writing, what it means for Belshazzar and consequences for him. Belshazzar immediately makes Daniel the third highest ruler in the kingdom anyway. The last two verses state that that very night Belshazzar was slain and Darius the Mede received the kingdom, being about sixty two years old.

Belshazzar in Later Jewish Tradition

Belshazzar appears in many works of classical Jewish rabbinic literature. The chronology of the three Babylonian kings is given in the Talmud (Megillah 11a-b) as follows: Nebuchadnezzar reigned forty-five years, Evil-merodach twenty-three, and Belshazzar was monarch of Babylonia for two years, being killed at the beginning of the third year on the fatal night of the fall of Babylon (Meg. 11b).

The references in the Talmud and the Midrash to Belshazzar emphasize his tyrannous oppression of his Jewish subjects. Several passages in the Prophets are interpreted as though referring to him and his predecessors. For instance, the passage, "As if a man did flee from a lion, and a bear met him" (Amos v. 19), the lion is said to represent Nebuchadnezzar, and the bear, equally ferocious if not equally courageous, is Belshazzar. (The book of Amos., nevertheless, is pre-Exilic.)

The three Babylonian kings are often mentioned together as forming a succession of impious and tyrannical monarchs who oppressed Israel and were therefore foredoomed to disgrace and destruction. The verse in Isaiah xiv. 22, And I will rise up against them, saith the Lord of hosts, and cut off from Babylon name and remnant and son and grandchild, saith the Lord, is applied by these interpretations to the trio: "Name" to Nebuchadnezzar, "remnant" to Evil-merodach, "son" to Belshazzar, and "grandchild" Vashti (ib.). The command given to Abraham to cut in pieces three heifers (Genesis 15:9) as a part of the covenant established between him and his God, was thus elucidated by readers of Daniel as symbolizing Babylonia, which gave rise to three kings, Nebuchadnezzar, Evil-merodach, and Belshazzar, whose doom is prefigured by this act of "cutting to pieces" (Midrash Genesis Rabbah xliv.).

The Midrash literature enters into the details of Belshazzar's death. Thus the later tradition states that Cyrus and Darius were employed as doorkeepers of the royal palace. Belshazzar, being greatly alarmed at the mysterious handwriting on the wall, and apprehending that someone in disguise might enter the palace with murderous intent, ordered his doorkeepers to behead anyone who attempted to force an entrance that night, even though such person should claim to be the king himself. Belshazzar, overcome by sickness, left the palace unobserved during the night through a rear exit. On his return the doorkeepers refused to admit him. In vain did he plead that he was the king. They said, "Has not the king ordered us to put to death any one who attempts to enter the palace, though he claim to be the king himself?" Suiting the action to the word, Cyrus and Darius grasped a heavy ornament forming part of a candelabrum, and with it shattered the skull of their royal master (Cant. R. iii. 4).

In art and popular culture

- Music

- Oratorio Il convito di Baldassarro by Pirro Albergati, composed in 1691.

- Oratorio Belshazzar by George Frideric Handel, composed in the late summer of 1744.

- Incidental music Belshazzar's Feast by Jean Sibelius, op. 51, composed in 1906.

- Cantata Belshazzar's Feast by Sir William Walton, composed in 1930-1.

- Singer/Songwriter Johnny Cash wrote a song titled "Belshazar", based on the Biblical story. It was recorded at Sun Studio in Memphis, Tennessee in 1957. It was covered by Bob Dylan and The Band as "Belchezaar", on sessions for The Basement Tapes recorded in Woodstock, NY.

- The Jewish songwriter Harold Rome wrote, for the musical "Pins and Needles" in 1937, a gospel song, "Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin," which made the analogy between Belshazzar and Hitler, saying the former "didn't pay no income taxes:/The big shot of the Babylon-Jerusalem Axis." Interpreting the writing on the wall, Daniel sums it up tersely: "King, stop your fightin' and your flauntin'./You been weighed, and you're found wantin'."

- The Austin, Texas band Sound Team references Belshazzar with the lyric: "But I don't have to sleep at Belshazzar's house anymore / Gave up the center line" on the track "No More Birthdays" off their Movie Monster LP.

- The Norwegian singer/songwriter Eth Eonel wrote a song titled "Belsassar", which was released in 2011 on the album "Drawing Lines (1989)". The song lays out an aquatic version of Belshazzar's feast, in which Belshazzar is a fish, and "the writing on the wall" becomes "the writing in the sand".

- Literature

- The fourteenth-century poem Cleanness by the Pearl Poet recounts the feast and subsequent events as a warning against spiritual impurity.

- "Vision of Belshazzar" by the poet Lord Byron chronicles both the feast and Daniel's pronunciation.

- Robert Frost's poem, "The Bearer of Evil Tidings", is about a messenger headed to Belshazzar's court to deliver the news of the king's imminent overthrow. Remembering that evil tidings were a "dangerous thing to bear," the messenger flees to the Himalayas rather than facing the monarch's wrath.

- Emily Dickinson's poem "Belshazzar had a letter," #1459 from the Poems of Emily Dickinson is about Belshazzar's immortal correspondence. Her poem was written in 1879.

- Herman Melville's book "Moby Dick" at chapter 99 has the first mate Starbuck murmer to himself "The old man seems to read Belshazzar's awful writing" as he spies Ahab speaking to the doubloon he had nailed to the mast of the Pequod.

- In his novel Sister Carrie, Theodore Dreiser entitles a chapter "The Feast of Belshazar - A Seer to Translate" in which the gluttony of turn-of-the-century New York City is highlighted.

- Belshazzar was the title of a 1930 novel by H. Rider Haggard.

- Robert E. Howard, creator of Conan the Barbarian, liked to incorporate historical names into his pseudo-historical stories. He wrote a (non-Conan) adventure story, "Blood of Belshazzar" which Roy Thomas adapted into a Conan story in Marvel Comics' Conan the Barbarian #27 as "The Blood of Bel-Hissar". Howard also used the name of 'Nabonidus' (father of Belshazzar) in the Conan tale "Rogues in the House" which appeared in Marvel's Conan the Barbarian #11.

In Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice, Portia disguises herself as Balthazar in Act IV, scene i.

- Heinrich Heine wrote a short poem entitled "Belsatzar" in his collection "Junge Leiden".[6]

- In Fazil Iskander's novel "Sandro of Chegem", one of the chapters depicting a dinner involving an Abkhazian dance ensemble and Stalin is titled "Belshazzar's Feast".

- Paintings, drawings

- Belshazzar's Feast is a painting by Rembrandt van Rijn created around 1635.

- Belshazzar's Feast is a painting by John Martin from c. 1821.

- In The Hand-Writing upon the Wall (1803), James Gillray caricatured Napoleon in the role of Belshazzar.

- During the 1884 United States presidential campaign, Republican candidate James G. Blaine dined at a New York City restaurant with some wealthy business executives including "Commodore" Vanderbilt, Jay Gould, etc. This was featured in newspapers, with a drawing illustrating "The Feast of Belshazzar Blaine..." On the wall in the background was written "Mene Mene Tekel Upharsin".

- Film, television

- Belshazzar is a main character in one of the four stories presented in D. W. Griffith's film Intolerance (1916).

- Belshazzar is played by Michael Ansara in the 1953 William Castle film, Slaves of Babylon.

- Belshazzar was featured in the Season one, Episode two of the Nickelodeon game show Legends of the Hidden Temple, entitled "The Golden Cup of Belshazzar."

See also

- Biblical archaeology (excavations and artifacts)

- Cylinder of Nabonidus

- List of artifacts significant to the Bible

References

Cite error: Invalid <references> tag;

parameter "group" is allowed only.

<references />, or <references group="..." />Further reading

- Oppenheim, A. Leo (1977), Ancient Mesopotamia: Portrait of a Dead Civilization (Rev. ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-63186-9.

- Gaston, T. E. (2009), Historical Issues in the Book of Daniel, Oxford: Taanathshiloh, ISBN 978-0-9561540-0-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Belshazzar. |

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Belshazzar

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Baltasar

- Articles needing additional references from April 2011

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- All articles needing additional references

- Commons category template with no category set

- Commons category with page title different than on Wikidata

- 6th-century BC biblical rulers

- Babylonia

- Monarchs of the Hebrew Bible

- Book of Daniel

- CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list