Chaldean people

|

| |||||||||

| Total population | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesopotamia 2–3.3 million[2] | |||||||||

| Regions with significant populations | |||||||||

| | 300,000[3] | ||||||||

| | 400,000[4] | ||||||||

| | 20,000[5][6] | ||||||||

| | 15,000–25,100[5][7][8] | ||||||||

| | 100,000[9] | ||||||||

| | 110,807–400,000[10][11] | ||||||||

| | 100,000–150,000[12] | ||||||||

| | 100,000[13] | ||||||||

| | 24,505–60,000[14][15] | ||||||||

| | 39,000[16] | ||||||||

| | 20,000{{ }} | ||||||||

| | 16,000[17] | ||||||||

| | 15,000[18] | ||||||||

| | 10,911[19] | ||||||||

| | 10,810[20] | ||||||||

| | 10,000[18] | ||||||||

| | 10,000[18] | ||||||||

| | 6,390[21] | ||||||||

| | 6,000[22] | ||||||||

| | 3,299[23] | ||||||||

| | 3,143[24] | ||||||||

| | 3,000[18] | ||||||||

| | 2,769[25] | ||||||||

| | 1,683[26] | ||||||||

| | 1,500[27] | ||||||||

| | 350–800[28][29] | ||||||||

| | 300[30] | ||||||||

| Languages | |||||||||

|

Aramaic: Neo-Aramaic (also various Neo-Aramaic dialects) | |||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||

| † Chaldean Christianity | |||||||||

| Related ethnic groups | |||||||||

| Mhallami, Maronites | |||||||||

The Chaldeans (Syriac: Kaldaya), also known as Syriacs, Syrians, Arameans (see names of Syriac Christians), are an ethnic group whose origins lie in ancient Mesopotamia. They speak, read, and write distinct dialects of Chaldean language Eastern Aramaic exclusive to Mesopotamia and its immediate surroundings.

Today that ancient territory is part of several nations: the north of Iraq, part of southeast Turkey and northeast Syria. They are indigenous to, and have traditionally lived all over what is now Iraq, northeast Syria, northwest Iran, and southeastern Turkey.[31][better source needed] Most Chaldeans speak an Eastern Aramaic language whose subdivisions include Chaldean Neo-Aramaic, Chaldean and Kaldeya.[32]

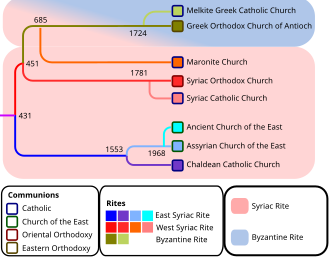

The Chaldeans are a Christian people, most of them following various Eastern Rite Churches. Divisions exist between the speakers of Northeastern Neo-Aramaic, who mostly belong to the Chaldean Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church and have been historically concentrated in what is now northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey, and speakers of Central Neo-Aramaic, who traditionally belong to the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church and are indigenous to what is now southern Turkey, northern Syria and northern Iraq.

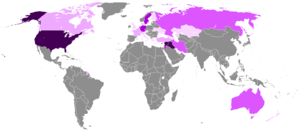

Many have migrated to the Caucasus, North America, Australia and Europe during the past century or so. Diaspora and refugee communities are based in Europe (particularly Sweden, Germany, Netherlands, and France), North America, New Zealand, Lebanon, Armenia, Georgia,[33] southern Russia, Israel, Azerbaijan and Jordan.

Emigration was triggered by such events as the Chaldean Genocide by the Ottoman Empire during World War I, the Simele massacre in Iraq (1933), the Islamic revolution in Iran (1979), Arab Nationalist Baathist policies in Iraq and Syria, the Al-Anfal Campaign of Saddam Hussein,[34] and Kurdish nationalist policies in northern Iraq.

Most recently, the Iraq War has displaced the regional Chaldean community, as its people have faced ethnic and religious persecution at the hands of Islamic extremists and Arab and Kurdish nationalists. Of the one million or more Iraqis reported by the United Nations to have fled Iraq since the occupation, nearly 40% are Chaldean, although Chaldeans comprised around 3% of the pre-war Iraqi population.[35][36][37] According to a 2013 report by a Chaldean Syriac Popular Council official, it is estimated that only 300,000 Chaldeans remain in Iraq.[3]

Contents

[hide]History

|

Pre-Christian history

Arab conquest

The Chaldeans initially experienced some periods of religious and cultural freedom interspersed with periods of severe religious and ethnic persecution after Arab Islamic invasion and conquest of the 7th century AD. As heirs to ancient Mesopotamian civilisation, they also contributed hugely to the Arab Islamic Civilization during the Umayyads and the Abbasids by translating works of Greek philosophers to Chaldean language and afterwards to Arabic. They also excelled in philosophy, science and theology (such as Tatian, Bar Daisan, Babai the Great, Nestorius, Toma bar Yacoub etc.) and the personal physicians of the Abbasid Caliphs were often Chaldean Christians such as the long serving Bukhtishu dynasty.[38]

However, despite this, indigenous Chaldeans became second class citizens in a greater Arab Islamic state, and those who resisted Arabization and conversion to Islam were subject to severe religious, ethnic and cultural discrimination, and had certain restrictions imposed upon them.[39] Chaldeans were excluded from specific duties and occupations reserved for Muslims, they did not enjoy the same political rights as Muslims, their word was not equal to that of a Muslim in legal and civil matters, as Christians they were subject to payment of a special tax (jizyah), they were banned from spreading their religion further or building new churches in Muslim ruled lands, but were also expected to adhere to the same laws of property, contract and obligation as the Muslim Arabs.[40]

As non-Islamic proselytising was punishable by death under Sharia law, the Chaldeans were forced into preaching in Transoxania, Central Asia, India, Mongolia and China where they established numerous churches. The Church of the East was considered to be one of the major Christian powerhouses in the world, alongside Latin Christianity in Europe and the Byzantine Empire.[41]

From the 7th century AD onwards Mesopotamia saw a steady influx of Arabs, Kurds and other Iranian peoples,[42] and later Turkic peoples, and the indigenous population retaining native Mesopotamian culture, identity, language, religion and customs were steadily marginalised and gradually became a minority in their own homeland.[43]

The process of marginalisation was largely completed by the massacres of indigenous Chaldean Christians and other non-Muslims in Mesopotamia and its surrounds by Tamerlane the Mongol in the 14th century AD, and it was from this point that the ancient Chaldean capital of Assur was finally abandoned by Chaldeans.[44]

However, many Chaldean Christians survived the various massacres and pogroms, and resisted the process of Arabization and Islamification, retaining a distinct Mesopotamian identity, Mesopotamian Aramaic language and written script. The modern Chaldeans, Syriac-Arameans or Chaldeans of today are descendants of the indigenous inhabitants of Mesopotamia, who refused to be converted to Islam or be culturally and linguistically Arabized.

Culturally, ethnically and linguistically distinct from, although both quite influencing on, and quite influenced by, their neighbours in the Middle East—the Arabs, Persians, Kurds, Turks, Jews and Armenians — the Chaldeans have endured much hardship throughout their recent history as a result of religious and ethnic persecution.

Mongolian and Turkic rule

The region came under the control of the Mongol Empire after the fall of Baghdad in 1258. The Mongol khans were sympathetic with Christians and did not harm them. The most prominent among them was probably Isa, a diplomat, astrologer, and head of the Christian affairs in the Yuan Dynasty in East Asia. He spent some time in Persia under the Ilkhans. The 14th century AD massacres of Timur in particular, devastated the Chaldean people. Timur's massacres and pillages of all that was Christian drastically reduced their existence. At the end of the reign of Timur, the Chaldean population had almost been eradicated in many places. Toward the end of the thirteenth century, Bar Hebraeus (or Bar-Abraya), the noted Chaldean scholar and hierarch, found "much quietness" in his diocese in Mesopotamia. Syria’s diocese, he wrote, was "wasted."

The region was later controlled by Turkic tribes such as the Aq Qoyunlu and Qara Qoyunlu. Seljuq and Arab emirates sought to extend their rule over the region as well.

From Iranian Safavid to confirmed Ottoman rule

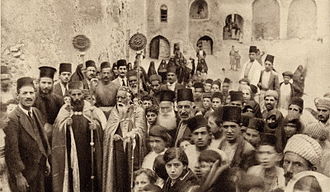

The Ottomans secured their control over Mesopotamia and Syria in the first half of the 17th century following the Ottoman–Safavid War (1623–39) and the resulting Treaty of Zuhab. Non-Muslims were organised into millets. Syriac Christians, however, were often considered one millet alongside Armenians until the 19th century, when Nestorian, Syriac Orthodox and Chaldeans gained that right as well.[45]

A religious schism amongs the Chaldeans took place in the mid to late 16th century. Dissent over the hereditary succession within the Chaldean Church of the East grew until 1552, when a group of Chaldean bishops, from the northern regions of Amid and Salmas, elected a priest, Mar Yohannan Sulaqa, as a rival patriarch. To look for a bishop of metropolitan rank to consecrate him patriarch, Sulaqa traveled to the pope in Rome and entered into communion with the Catholic Church. In 1553 he was consecrated bishop and elevated to the rank of patriarch taking the name of Mar Shimun VIII. He was granted the title of "Patriarch of the Chaldeans," and his church was named the Church of Athura and Mosul.[46]

Mar Shimun VIII Yohannan Sulaqa returned to northern Mesopotamia in the same year and fixed his seat in Amid. Before being put to death by the partisans of the Church of the East patriarch of Alqosh,[47]:57 he ordained five metropolitan bishops thus beginning a new ecclesiastical hierarchy: the patriarchal line known as the Shimun line. The area of influence of this patriarchate soon moved from Amid east, fixing the See, after many places, in the isolated Chaldean village of Qochanis. Although this new church eventually drifted away from Rome by 1600 AD and reentered communion with the Chaldean Church, the archbishop of Amid reinstated relations with Rome in 1672 AD, giving birth to the modern Chaldean Catholic Church.

In the 1840s many of the Chaldeans living in the mountains of Hakkari in the south eastern corner of the Ottoman Empire were massacred by the Kurdish emirs of Hakkari and Bohtan.[48]

Another major massacre of Chaldeans (and Armenians) in the Ottoman Empire occurred between 1894 and 1897 AD by Turkish troops and their Kurdish allies during the rule of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. The motives for these massacres were an attempt to reassert Pan-Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, resentment at the comparative wealth of the ancient indigenous Christian communities, and a fear that they would attempt to secede from the tottering Ottoman Empire. Chaldeans were massacred in Diyarbakir, Hasankeyef, Sivas and other parts of Anatolia, by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. These attacks caused the death of over thousands of Chaldeans and the forced "Ottomanisation" of the inhabitants of 245 villages. The Turkish troops looted the remains of the Chaldean settlements and these were later stolen and occupied by Kurds. Unarmed Chaldean women and children were raped, tortured and murdered.[49]

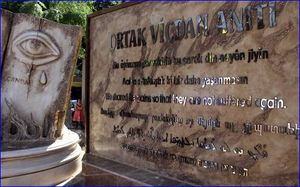

World War I and Aftermath

The most significant recent persecution against the Chaldean population was the Chaldean genocide which occurred during the First World War. About 300,000 Chaldeans were estimated to have been slaughtered by the armies of the Ottoman Empire and their Kurdish allies, totalling up to two-thirds of the entire Chaldean population. This led to a large-scale migration of Turkish-based Chaldean people into countries such as Syria, Iran, and Iraq (where they were to suffer further violent assaults at the hands of the Arabs and Kurds), as well as other neighbouring countries in and around the Middle East such as Armenia, Georgia and Russia.[50][51][52][53]

In reaction to the Chaldean Genocide and lured by British and Russian promises of an independent nation, the Chaldeans led by Agha Petros and Malik Khoshaba of the Bit-Tyari tribe, fought alongside the allies against Ottoman evil forces. Despite being heavily outnumbered and outgunned the Chaldeans fought successfully, scoring a number of victories over the Turks and Kurds. This situation continued until their Russian allies left the war, and Armenian resistance broke, leaving the Chaldeans surrounded, isolated and cut off from lines of supply.

Modern history

The majority of Chaldean living in what is today modern Turkey were forced to flee to either Syria or Iraq after the Turkish victory during the Turkish War of Independence.

The Chaldean Levies were founded by the British in 1928, with ancient Chaldean military rankings such as Rab-shakeh, Rab-talia and Tartan, being revived for the first time in millennia for this force. The Chaldeans were prized by the British rulers for their fighting qualities, loyalty, bravery and discipline,[54] and were used to help the British put down insurrections among the Arabs and Kurds. During World War II, eleven Chaldean companies saw action in Palestine and another four served in Cyprus. The Parachute Company was attached to the Royal Marine Commando and were involved in fighting in Albania, Italy and Greece. The Chaldean Levies played a major role in subduing the pro-Nazi Iraqi forces at the battle of Habbaniya in 1941.

However, this cooperation with the British was viewed with suspicion by some leaders of the newly formed Kingdom of Iraq. The tension reached its peak shortly after the formal declaration of independence when hundreds of Chaldean civilians were massacred during the Simele Massacre by the Iraqi Army in August 1933. The events lead to the expulsion of Shimun XXIII Eshai the Catholicos Patriarch of the Church of the East to the United States where resided until his death in 1975.[55][56]

The Ba'ath Party seized power in Iraq and Syria in 1963, which introduced laws that aimed at suppressing the Chaldean national identity, the Arab Nationalist policies of the Ba'athists included renewed attempts to forcibly "Arabize" the indigenous Chaldeans. The giving of traditional Chaldean/Akkadian names and East Aramaic/Syriac versions of Biblical names was banned, Chaldean schools, political parties, churches and literature were repressed and Chaldeans were heavily pressured into identifying as Arab Christians. The Ba'athist government refused to recognise Chaldeans as an ethnic group, and fostered divisions among the ethnic Chaldeans along religious lines (e.g. Chaldean Church of the East vs Chaldean Catholic Church vs Syriac Orthodox Church vs Chaldean Protestant).[57]

The al-Anfal Campaign of 1986–1989 in Iraq was predominantly aimed at Kurds. However, 2,000 Chaldeans were murdered through its gas campaigns; over 31 towns and villages and 25 Chaldean monasteries and churches were razed to the ground; a number of Chaldeans were murdered; others were deported to large cities, and their land and homes then being appropriated by Arabs and Kurds.[58][59]

21st Century

Since the 2003 Iraq War social unrest and anarchy have resulted in the unprovoked persecution of Chaldeans in Iraq, mostly by Islamic extremists, (both Shia and Sunni), and to some degree by Kurdish nationalists. In places such as Dora, a neighborhood in southwestern Baghdad, the majority of its Chaldean population has either fled abroad or to northern Iraq, or has been murdered.[60]

Islamic resentment over the United States' occupation of Iraq, and incidents such as the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons and the Pope Benedict XVI Islam controversy, have resulted in Muslims attacking Chaldean Christian communities. Since the start of the Iraq war, at least 46 churches and monasteries have been bombed.[61]

The Syriac Military Council is a Chaldean/Syriac military organisation in Syria. The establishment of the organisation was announced on 8 January 2013. According to the Syriac Military Council the goal of the organisation is to stand up for the national rights of Syriacs and to protect the Syriac people in Syria. It intends to work together with the other communities in Syria to change the current government of Bashar al-Assad. The organisation will fight mostly in the densely populated Syriac areas of the Governorates of Aleppo, Damascus, Al-Hasakah, Latakia and Homs.[62]

Demographics

Homeland

The Chaldeans are considered to be one of the indigenous people in the Middle East. Their homeland was thought to be located in the area around the Tigris and Euphrates. Chaldeans are traditionally from Iraq, south eastern Turkey, north western Iran and north eastern Syria. There is a significant Chaldean population in Syria, where an estimated 877,000 Chaldeans live.[63]

In Tur Abdin, known as a homeland for Chaldeans, there are only 3000 left,[64] and an estimated 25,000 in all of Turkey.[65] After the 1915 Chaldean genocide many Chaldeans/Syriacs also fled into Lebanon, Jordan, Iran, Iraq and into the Western world.

The Chaldean/Syriac people can be divided along geographic, linguistic, and denominational lines, the three main groups being:

- the "Western" or "Jacobite" group of Syria, and central eastern Anatolia (Syriac Orthodox Church & Syriac Catholic Church);

- the "Eastern" group of Iraq, northeast Syria south eastern Turkey, northwest Iran and Armenia ( Church of the East & Ancient Church of the East);

- the "Chaldean Christian" or "Chaldean Catholic"/Chaldo-Chaldean group of northern and central Iraq, northern Iran, and eastern Anatolia (Chaldean Catholic Church); Chaldean followers of the Chaldean Catholic church make up the majority of Iraqi Christian population since rejoining to Catholicism from the Chaldean Church of the East in the 16th century.

Persecution

Due to their Christian faith and ethnicity, the Chaldeans have been persecuted since their adoption of Christianity. During the reign of Yazdegerd I, Christians in Persia were viewed with suspicion as potential Roman subversives, resulting in persecutions while at the same time promoting Nestorian Christianity as a buffer between the Churches of Rome and Persia. Persecutions and attempts to impose Zoroastrianism continued during the reign of Yazdegerd II.[66][67]

During the eras of Mongol rule under Genghis Khan and Timur, there was indiscriminate slaughter of tens of thousands of Chaldeans and destruction of the Chaldean population of northwestern Iran and central and northern Iran.[68]

More recent persecutions since the 19th century include the Massacres of Badr Khan, the Massacres of Diyarbakır (1895), the Adana Massacre, the Chaldean Genocide, the Simele Massacre, and the al-Anfal Campaign.

Chaldean Diaspora

Since the Chaldean genocide, many Chaldeans have fled their homelands for a more safe and comfortable life in the West. Since the beginning of the 20th century, the Chaldean population in the Middle East has decreased dramatically. As of today there are more Chaldeans in Europe, North America, and Australia than in their naive homeland of Mesopotamia, also known as Iraq, Syria and Southern Turkey. Read more about the Chaldean Diaspora.

A total of 550,000 Chaldeans live in Europe.[69] Large Chaldean and Syriac diaspora communities can be found in Germany, France, Belgium, Sweden, the USA, and Australia. The largest Chaldean and Syriac diaspora communities are those of Michigan and California.

Chaldean Identity

Chaldeans have several churches (see below). They speak, and many can read and write, dialects of Chaldean Neo-Aramaic.[71]

In certain areas of the Chaldean homeland, identity within a community depends on a person's village of origin (see List of Chaldean villages) or Christian denomination rather than their Chaldean ethnic commonality, for instance Chaldean Catholic.

Neo-Aramaic exhibits remarkably conservative features compared with Imperial Aramaic.[72]

Other Related Self-designation

The communities of indigenous Chaldean Neo-Aramaic-speaking people of Iraq, Israel, Palestine, Syria, Iran, Turkey and Lebanon and the surrounding areas advocate different terms for ethnic self-designation.

- "Chaldeans", after the ancient Mesopotamia, are mostly followers of the Chaldean Church of the East or Chaldean Nestorian, the Ancient Church of the East, followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church and Chaldean non Catholics. ("Chaldeans"),[73] and some communities of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church ("Chaldeans"). Those identifying with Chaldea, and with Mesopotamia in general, tend to be from Iraq, northeastern Syria; southeastern Turkey, Iran, Armenia, Georgia; southern Russia and Azerbaijan. They are indeed of Chaldean/Mesopotamian heritage as they are clearly of pre-Arab and pre-Islamic stock. Furthermore, there is no historical evidence or proof to suggest the indigenous Mesopotamians were wiped out; Chaldea existed as a specifically named region until the second half of the 7th century AD. Most speak Chaldean and the Mesopotamian dialects of Neo-Aramaic. Chaldean nationalism emphatically connects Modern Chaldeans to the population of ancient Mesopotamia and the Neo-Chaldean Empire. A historical basis of this sentiment was disputed by a few early historians,[74] but receives strong support from modern Sumeriologists like Robert D. Biggs and Giorgi Tsereteli [75]

- "Chaldeans", after ancient Chaldea, are followers of the Chaldean Catholic Church who are mainly based in Mesopotamia Iraq and reside in many global countries such as the United States. Chaldean is a distinct Chaldean ethnic and native identity of Mesopotamia.

- "Syriacs", advocated by followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church, Syriac Catholic Church and to a much lesser degree Maronite Church. Those self identifying as Syriacs tend to be from Syria as well as south central Turkey. The term Syriac is the subject of some controversy, as it is generally accepted by most scholars that it is a Luwian and Greek. The discovery of the Çineköy inscription seems to settle conclusively in favour of Chaldean being the origin of the terms Syria and Syriac. However, Poseidonios (ca. 135 BC – 51 BC), from the Syrian Apamea, was a Greek Stoic philosopher, politician, astronomer, geographer, historian, and teacher who says that the Syrians call themselves Arameans.[nb 1]. At the same time historians, geographers and philosophers like Herodotos, Strabo, and Justinus mention that Chaldeans were afterwards called Syrians.[nb 2].

- "Arameans", after the ancient Aram-Naharaim, advocated by some followers of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Syriac Catholic Church in western, northwestern, southern and central Syria as well as south central Turkey. The term Aramean is sometimes expanded to "Syriac-Aramean".

In addition Western Media often makes no mention of any ethnic identity of the Christian people of the region and simply call them Christians, Iraqi Christians, Iranian Christians, Syrian Christians, Turkish Christians, etc. This label is rejected by Chaldeans/Chaldeans/Syriacs since it erroneously implies no difference other than theological with the Muslim Arabs, Kurds, Turks, Iranians and Azeris of the region.

Chaldean and Syriac or Syrian are Same People

As early as the 8th century BC Luwian and Cilician subject rulers referred to their Chaldean overlords as Syrian, a western Indo-European bastardisation of the true term Chaldean. This corruption of the name took hold in the Hellenic lands to the west of the Chaldean Babylonian Empire, thus during Greek Seleucid rule from 323 BC the name Chaldea was altered to Syria, and this term was also applied to Aramea to the west which had been an Chaldean colony. When the Seleucids lost control of Chaldea to the Parthians they retained the corrupted term (Syria), applying it to ancient Aramea, while the Parthians called Chaldea, a Parthian form of the original name. It is from this period that the Syrian vs Chaldean controversy arises. Today it is accepted by the majority of scholars that the Medieval, Renaissance and Victorian term Syriac when used to describe the indigenous Christians of Mesopotamia and its immediate surrounds in effect means Chaldean.[76]

The modern terminological problem goes back to colonial times, but it became more acute in 1946, when with the independence of Syria, the adjective Syrian referred to an independent state. The controversy isn't restricted to exonyms like English "Chaldean" vs. "Aramaean", but also applies to self-designation in Neo-Aramaic, the minority "Aramaean" faction endorses both Sūryāyē ܣܘܪܝܝܐ and Ārāmayē ܐܪܡܝܐ

The question of ethnic identity and self-designation is sometimes connected to the scholarly debate on the etymology of "Syria". The question has a long history of academic controversy, but majority mainstream opinion currently strongly favours that Syria is indeed ultimately derived from the Chaldean term 𒀸𒋗𒁺 𐎹 Kaldaya.[77][78] Meanwhile, some scholars has disclaimed the theory of Syrian being derived from Chaldean as "simply naive", and detracted its importance to the naming conflict.[79]

Rudolf Macuch points out that the Eastern Neo-Aramaic press initially used the term "Syrian" (suryêta) and only much later, with the rise of nationalism, switched to "Chaldean" (atorêta).[80] According to Tsereteli, however, a Georgian equivalent of "Chaldeans" appears in ancient Georgian, Armenian and Russian documents.[81] This correlates with the theory of the nations to the East of Mesopotamia knew the group as Chaldeans, while to the West, beginning with Greek influence, the group was known as Syrians. Syria being a Greek corruption of Chaldea.

The debate appears to have been settled by the discovery of the Çineköy inscription in favour of Syria being derived from Chaldea.

The Çineköy inscription is a Hieroglyphic Luwian-Phoenician bilingual, uncovered from Çineköy, Adana Province, Turkey (ancient Cilicia), dating to the 8th century BC. Originally published by Tekoglu and Lemaire (2000),[82] it was more recently the subject of a 2006 paper published in the Journal of Near Eastern Studies, in which the author, Robert Rollinger, lends support to the age-old debate of the name "Syria" being derived from "Chaldea" (see Etymology of Syria).

The object on which the inscription is found is a monument belonging to Urikki, vassal king of Hiyawa (i.e., Cilicia), dating to the eighth century BC. In this monumental inscription, Urikki made reference to the relationship between his kingdom and his Chaldean overlords. The Luwian inscription reads "Sura/i" whereas the Phoenician translation reads ’ŠR or "Ashur" which, according to Rollinger (2006), "settles the problem once and for all".

Culture

Chaldean culture is largely influenced by Christianity. Main festivals occur during religious holidays such as Easter and Christmas. There are also secular holidays such as Kha b-Nisan (vernal equinox).[83]

People often greet and bid relatives farewell with a kiss on each cheek and by saying "ܫܠܡܐ ܥܠܝܟ" Shlama/Shlomo lokh, which means: "Peace be upon you." Others are greeted with a handshake with the right hand only; according to Middle Eastern customs, the left hand is associated with evil. Similarly, shoes may not be left facing up, one may not have their feet facing anyone directly, whistling at night is thought to waken evil spirits, etc.[84]

There are many Chaldean customs that are common in other Middle Eastern cultures. A parent will often place an eye pendant on their baby to prevent "an evil eye being cast upon it".[85] Spitting on anyone or their belongings is seen as a grave insult.

Language

File:Chaldean Language Course.pdf

The Chaldean Language is native language of [Mesopotamia | Mesopotamia], the lingua franca in the later phase of the Neo- Chaldean Empire, displacing the East Semitic Chaldean dialect of Akkadian. Aramaic was the language of commerce, trade and communication and became the vernacular language of Chaldea in classical antiquity.[86][87][88]

By the 1st century AD, Akkadian was extinct, although some loaned vocabulary still survives in Chaldean Neo-Aramaic to this day.[89][90]

To the native Chaldean speaker, "Chaldean Langauge" and "Syriac" is usually called Soureth or Suret. A wide variety of dialects exist, including Chaldean Neo-Aramaic. All are classified as Chaldean Neo-Aramaic languages and are written using Chaldean script. Chaldeans also may speak one or more languages of their country of residence. Being stateless, Chaldeans also learn the language or languages of their adopted country, usually Arabic, Armenian, Persian or Turkish. In northern Iraq and western Iran, Turkish and Kurdish is widely spoken.

Recent archaeological evidence includes a statue from Syria with Akkadian and Aramaic inscriptions.[91] It is the oldest known Aramaic text.

Religion

Since the beginning of Christianity in 30 AD, Chaldeans are the first Christians of the world. Chaldeans currently belong to various Christian denominations such as the Church of the East, with an estimated 500,000 members,[92] the Chaldean Catholic Church, with about 1,500,000 members,[93] and the Syriac Orthodox Church (ʿIdto Suryoyto Triṣaṯ Šuḇḥo), which has between 1,000,000 and 4,000,000 members around the world (only some of whom are Chaldeans),[94] the Ancient Church of the East with some 100,000 members, and various Protestant churches, such as the Pentecostal Church with 25,000 adherents, and the Evangelical Church. While Chaldeans are predominantly Christians, a number are irreligious.

As of 2015[update] Mar Louis Sako, resident in Baghdad Iraq, was Patriarch of the Chaldeans Catholic Church, Mar Addai II, with headquarters in Baghdad, was Patriarch of the Ancient Church of the East, and Ignatius Zakka I Iwas was Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church, with headquarters in Damascus. Mar Emmanuel III Delly, the former Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic Church, was the first Patriarch to be elevated to Cardinal, joining the college of cardinals in November 2007.

Many members of the following churches consider themselves Chaldean. Ethnic identities are often deeply intertwined with religion, a legacy of the Ottoman Millet system. The group is traditionally characterized as adhering to various churches of Syriac Christianity and speaking Neo-Aramaic languages. It is subdivided into:

- adherents of the East Syrian Rite also known as Nestorians

- adherents of the Church of the East & Ancient Church of the East

- adherents of the Chaldean Catholic Church.

- adherents of the West Syrian Rite also known as Jacobites

- adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church

- adherents of the Syriac Catholic Church

A small minority of Chaldeans of the above denominations accepted the Protestant Reformation in the 20th century, possibly due to British influences, and is now organized in the Evangelical Church, the Pentecostal Church and other Protestant Chaldean groups.

Baptism and First Communion are celebrated extensively, similar to a Bris or Bar Mitzvah in Jewish communities. After a death, a gathering is held three days after burial to celebrate the ascension to heaven of the dead person, as of Jesus; after seven days another gathering commemorates their death. A close family member wears only black clothes for forty days and nights, or sometimes a year, as a sign of mourning.

Music

The abooba ܐܒܘܒܐ (basic flute) and ṭavla ܛܒ݂ܠܐ (large two-sided drum) became the most common musical instruments for tribal music. Some well known Chaldean/Syriac singers in modern times are Majid Kekka, Sargon Gabriel, Habib Mousa, Josef Özer, Janan Sawa, Klodia Hanna, Juliana Jendo

The first International Chaldean Music Festival was held in Lebanon from 1 August until 4 August 2008 for Chaldean people internationally. Chaldeans are also involved in western contemporary music, such as Rock/Metal (Melechesh), Rap (Timz) and Techno/Dance (Aril Brikha).

Dance

Chaldeans have numerous traditional dances which are performed mostly for special occasions such as weddings. Chaldean dance is a blend of both ancient indigenous and general near eastern elements.

Festivals

Chaldean festivals tend to be closely associated with their Christian faith, of which Easter is the most prominent of the celebrations. Chaldean/Syriac members of the Chaldean Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church and Syriac Catholic Church follow the Gregorian calendar and as a result celebrate Easter on a Sunday between March 22 and April 25 inclusively. While Chaldean/Syriac members of the Syriac Orthodox Church and Ancient Church of the East celebrate Easter on a Sunday between April 4 and May 8 inclusively on the Gregorian calendar (March 22 and April 25 on the Julian calendar). During Lent Chaldean/Syriacs are encouraged to fast for 50 days from meat and any other foods which are animal based.

Chaldeans celebrate a number of festivals unique to their culture and traditions as well as religious ones:

- Kha b-Nisan ܚܕ ܒܢܝܣܢ, the Chaldean new year (AKA AKITU), traditionally on April 1, though usually celebrated on January 1. Chaldeans usually wear traditional costumes and hold social events including parades and parties, dancing, and listening to poets telling the story of creation.[95]

- Sauma d-Ba'utha ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܝܐ, the Nineveh fast. It is a three-day period of fasting and prayer.[96]

- Somikka, the Chaldean version of Halloween, traditionally meant to scare children into fasting during Lent.

- Sharra d'Mart Maryam, usually on August 15, a festival and feast celebrating St. Mary with games, food, and celebration.[97]

- Other Sharras (special festivals) include: Sharra d'Mart Shmuni, Sharra d'Mar Shimon Bar-Sabbaye, Sharra d'Mar Mari, and Shara d'Mar Zaia, Mar Bishu, Mar Sawa, Mar Sliwa, and Mar Odisho

- Yoma d'Sah'deh (Day of Martyrs), commemorating the thousands massacred in the Simele Massacre and the hundreds of thousands massacred in the Chaldean Genocide.

Chaldeans also practice unique marriage ceremonies. The rituals performed during weddings are derived from many different elements from the past 7,300 years. An Chaldean wedding traditionally lasted a week. Today, weddings in the Chaldean homeland usually last 2–3 days; in the Chaldean diaspora they last 1–2 days.

Traditional clothing

Chaldean clothing varies from village to village. Clothing is usually blue, red, green, yellow, and purple; these colors are also used as embroidery on a white piece of clothing. Decoration is lavish in Chaldean costumes, and sometimes involves jewellery. The conical hats of traditional Chaldean dress have changed little over millennia from those worn in ancient Mesopotamia, and until the 19th and early 20th centuries the ancient Mesopotamian tradition of braiding or platting of hair, beards and moustaches was still common place.

Cuisine

Chaldean cuisine is similar to other Middle Eastern cuisines. It is rich in grain, meat, potato, cheese, bread and tomato. Typically rice is served with every meal, with a stew poured over it. Tea is a popular drink, and there are several dishes of desserts, snacks, and beverages. Alcoholic drinks such as wine and wheat beer are organically produced and drunk.

See also

Notes

Cite error: Invalid <references> tag;

parameter "group" is allowed only.

<references />, or <references group="..." />References

Cite error: Invalid <references> tag;

parameter "group" is allowed only.

<references />, or <references group="..." />Further reading

- Aphram I Barsoum, Patriarch (1943). The Scattered Pearls.

- Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). The Hidden Pearl: The Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film. ISBN 1-931956-99-5.

- De Courtis, Sėbastien (2004). The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Arameans (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press. ISBN 978-1-59333-077-4.

- Chaldeans in Detroit. Arcadia Publishing. 2014.

- Empty citation (help)

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module `Module:Citation/CS1/Suggestions' not found.

- Henrich, Joseph; Henrich, Natalie (May 2007). Why Humans Cooperate: A Cultural and Evolutionary Explanation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-531423-9.

- Hollerweger, Hans (1999). Tur Abdin: A Homeland of Ancient Syro-Aramaean Culture (in English, German, and Turkish). Österreich. ISBN 3-9501039-0-2.

- Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. I: The Ancient Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film.

- Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. II: The Heirs of the Ancient Aramaic Heritage. Trans World Film.

- Taylor, David; Brock, Sebastian (9 September 2002). Vol. III: At the Turn of the Third Millennium; The Syrian Orthodox Witness. Trans World Film.

External links

- Chaldeans of Mesopotamia (2015). Native Chaldean People of Mesopotamia Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran.

<ref> tag;

no text was provided for refs named ReferenceABased on interviews with community informants, this paper explores socialization for ingroup identity and endogamy among Chaldeans in the United States. The Chaldeans descent from the population of ancient Mesopotamia (founded in the 24th century BC), and have lived as a linguistic, political, religious, and ethnic minority in Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey since the fall of the Chaldean Empire in 645 BC. Practices that maintain ethnic and cultural continuity in the Near East, the United States and elsewhere include language and residential patterns, ethnically based Christian churches characterized by unique holidays and rites, and culturally specific practices related to life-cycle events and food preparation. The interviews probe parental attitudes and practices related to ethnic identity and encouragement of endogamy. Results are being analyzed.

The survival of the Chaldean people will always remain a unique and striking phenomenon in ancient history. Other, similar kingdoms and empires have indeed passed away but the people have lived on. ... No other land seems to have been sacked and pillaged so completely as was Chaldea .

<ref> tag;

no text was provided for refs named Who_are_the_Chaldeans|url= value (help) (PDF). Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 283–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

|title= (help)[dead link]

<ref> tag;

no text was provided for refs named cultureofiran.com

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "nb", but no corresponding <references group="nb"/> tag was found, or a closing </ref> is missing

- Pages with script errors

- "Related ethnic groups" needing confirmation

- All pages needing factual verification

- Wikipedia articles needing factual verification from January 2015

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Articles containing potentially dated statements from 2015

- All articles containing potentially dated statements

- Pages with empty citations

- CS1 German-language sources (de)

- CS1 Turkish-language sources (tr)

- Chaldean people

- Ancient peoples

- Ethnic groups in Iran

- Ethnic groups in Iraq

- Ethnic groups in Syria

- Ethnic groups in Turkey

- Ethnic groups in the Middle East

- Fertile Crescent

- Semitic peoples

- History of Chaldeans

- Indigenous peoples of Western Asia

- Pages with citations using unnamed parameters

- Pages using web citations with no URL

- Pages using citations with accessdate and no URL

- CS1 maint: Multiple names: authors list

- Pages with URL errors

- Pages with citations lacking titles

- Pages with citations having bare URLs

- All articles with dead external links

- Articles with dead external links from September 2010