Difference between revisions of "Nebuchadnezzar II"

m (1 revision imported) |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

{{Lead too short|date=November 2017}} | {{Lead too short|date=November 2017}} | ||

| − | '''Nebuchadnezzar II''' (from [[Akkadian]] {{cuneiform|akk|𒀭𒀝𒆪𒁺𒌨𒊑𒋀}} ''<sup>[[DINGIR|d]]</sup>Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', {{hebrew Name|נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר|Nəvūkádne’ṣar|Neḇukáḏné’ṣār}}), meaning "O god [[Nabu]], preserve/defend my firstborn son") was king of [[Neo-Babylonian Empire|Babylon]] c. 605 BC – c. 562 BC, the longest and most powerful reign of any monarch in the Neo-Babylonian empire.{{sfn|Freedman|2000|p=953}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ancient.eu/Nebuchadnezzar_II/ |title=Nebuchadnezzar II |publisher=ancient.eu |accessdate=December 22, 2017}}</ref> | + | '''Nebuchadnezzar II''' (from [[Akkadian]] {{cuneiform|akk|𒀭𒀝𒆪𒁺𒌨𒊑𒋀}} ''<sup>[[DINGIR|d]]</sup>Nabû-kudurri-uṣur'', {{hebrew and Chaldean Name|נְבוּכַדְנֶאצַּר|Nəvūkádne’ṣar|Neḇukáḏné’ṣār}}), meaning "O god [[Nabu]], preserve/defend my firstborn son") was king of [[Neo-Babylonian Chaldean Empire|Babylon]] c. 605 BC – c. 562 BC, the longest and most powerful reign of any monarch in the Neo-Babylonian empire.{{sfn|Freedman|2000|p=953}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.ancient.eu/Nebuchadnezzar_II/ |title=Nebuchadnezzar II |publisher=ancient.eu |accessdate=December 22, 2017}}</ref> |

== Career == | == Career == | ||

[[File:Pergamon Museum Berlin 2007085.jpg|thumb|left|Building Inscription of King Nebuchadnezar II at the [[Ishtar Gate]]. An abridged excerpt says: ''"I (Nebuchadnezzar) laid the foundation of the gates down to the ground water level and had them built out of pure blue stone. Upon the walls in the inner room of the gate are bulls and dragons and thus I magnificently adorned them with luxurious splendor for all mankind to behold in awe."'']] | [[File:Pergamon Museum Berlin 2007085.jpg|thumb|left|Building Inscription of King Nebuchadnezar II at the [[Ishtar Gate]]. An abridged excerpt says: ''"I (Nebuchadnezzar) laid the foundation of the gates down to the ground water level and had them built out of pure blue stone. Upon the walls in the inner room of the gate are bulls and dragons and thus I magnificently adorned them with luxurious splendor for all mankind to behold in awe."'']] | ||

| − | [[File:Detail of a terracotta cylinder of Nebuchadnezzar II, recording the building and reconstruction works at Babylon. 604-562 BCE. From Babylon, Iraq, housed in the British Museum.jpg|thumb|Detail of a terracotta cylinder of Nebuchadnezzar II, recording the building and reconstruction works at Babylon. 604–562 BC. From Babylon, Iraq, housed in the British Museum]] | + | [[File:Detail of a terracotta cylinder of Nebuchadnezzar II, recording the building and reconstruction works at Babylon. 604-562 BCE. From Babylon, Iraq, housed in the British Museum.jpg|thumb|Detail of a terracotta cylinder of Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar II, recording the building and reconstruction works at Babylon. 604–562 BC. From Babylon, Iraq, housed in the British Museum]] |

| − | Nebuchadnezzar was the eldest son and successor of [[Nabopolassar]], | + | Nebuchadnezzar was the eldest son and successor of [[Nabopolassar]], a [[Chaldean Empire|Chaldean]] official who rebelled and established himself as king of Babylon in 620 BC; the dynasty he established ruled until 539 BC, when the [[Neo-Babylonian Empire]] was conquered by [[Cyrus the Great]].{{sfn|Bertman|2005|p=95}}{{sfn|Oates|1997|p=162}} Nebuchadnezzar is first mentioned in 607 BC, during the destruction of Babylon's arch-enemy of the cruel ancient Assyrian kings, at which point he was already crown Chaldean prince.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=182}} In 605 BC he and his ally [[Cyaxares]], ruler of the [[Medes]] and [[Persians]], led an army against the ancient Assyrians and Egyptians, who were then occupying Syria, and in the ensuing [[Battle of Carchemish]], [[Necho II]] defeated them and Syria and [[Phoenicia]] were brought under the control of the Chaldean people of Mesopotamia.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=182–183}} |

| − | [[Nabopolassar]] died in August {{citation needed|date=March 2018}} 605 BC, and Nebuchadnezzar returned to Babylon to ascend the throne.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=183}} For the next few years his attention was devoted to subduing his eastern and northern borders, and in 595/4 BC there was a serious but brief rebellion in Babylon itself.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233}} In 594/3 BC the army was sent again to the west, possibly in reaction to the elevation of [[Psammetichus II]] to the throne of Egypt.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233}} King [[Zedekiah]] of Judah attempted to organize opposition among the small states in the region, but his capital, [[Jerusalem]], was taken in 587 BC (the events are described in the Bible's [[Books of Kings]] and [[Book of Jeremiah]]).{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233–234}} In the following years Nebuchadnezzar incorporated [[Phoenicia]] and the | + | [[Nabopolassar]] died in August {{citation needed|date=March 2018}} 605 BC, and Nebuchadnezzar returned to Babylon to ascend the throne.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=183}} For the next few years his attention was devoted to subduing his eastern and northern borders, and in 595/4 BC there was a serious but brief rebellion in Babylon itself.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233}} In 594/3 BC the army was sent again to the west, possibly in reaction to the elevation of [[Psammetichus II]] to the throne of Egypt.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233}} King [[Zedekiah]] of Judah attempted to organize opposition among the small states in the region, but his capital, [[Jerusalem]], was taken in 587 BC (the events are described in the Bible's [[Books of Kings]] and [[Book of Jeremiah]]).{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=233–234}} In the following years Nebuchadnezzar incorporated [[Phoenicia]] and the provinces of [[Cilicia]] (southwestern Anatolia) into his empire and may have campaigned in Egypt.{{sfn|Wiseman|1991a|p=235–236}} In his last years Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar, "pay[ing] no heed to son or daughter," and was deeply suspicious of his sons.{{sfn|Foster|2009|p=131}} The kings who came after him ruled only briefly and [[Nabonidus]], apparently not of the royal family, was overthrown by the Persian conqueror [[Cyrus the Great]] less than twenty-five years after Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar's death. |

The ruins of Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon are spread over two thousand acres, forming the largest archaeological site in the [[Middle East]].{{sfn|Arnold|2005|p=96}} He enlarged the royal palace (including in it a public museum, possibly the world's first), built and repaired temples, built a bridge over the [[Euphrates]], and constructed a grand processional boulevard (the Processional Way) and gateway (the [[Ishtar Gate]]) lavishly decorated with glazed brick.{{sfn|Bertman|2005|p=96}} Each Spring [[equinox]] (the start of the New Year) the god [[Marduk]] would leave his city temple<!--clarify – unlikely that a fictitious deity went for a walk--> for a temple outside the walls, returning through the Ishtar Gate and down the Processional Way, paved with colored stone and lined with molded lions, amidst rejoicing crowds.{{sfn|Foster|2009|p=131}} | The ruins of Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon are spread over two thousand acres, forming the largest archaeological site in the [[Middle East]].{{sfn|Arnold|2005|p=96}} He enlarged the royal palace (including in it a public museum, possibly the world's first), built and repaired temples, built a bridge over the [[Euphrates]], and constructed a grand processional boulevard (the Processional Way) and gateway (the [[Ishtar Gate]]) lavishly decorated with glazed brick.{{sfn|Bertman|2005|p=96}} Each Spring [[equinox]] (the start of the New Year) the god [[Marduk]] would leave his city temple<!--clarify – unlikely that a fictitious deity went for a walk--> for a temple outside the walls, returning through the Ishtar Gate and down the Processional Way, paved with colored stone and lined with molded lions, amidst rejoicing crowds.{{sfn|Foster|2009|p=131}} | ||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

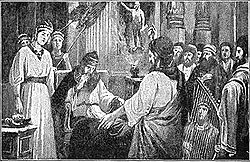

[[File:Daniel Interpreting Nebuchadnezzar's Dream.jpg|thumb|240px|Daniel Interpreting Nebuchadnezzar's Dream]] | [[File:Daniel Interpreting Nebuchadnezzar's Dream.jpg|thumb|240px|Daniel Interpreting Nebuchadnezzar's Dream]] | ||

| − | Nebuchadnezzar is an important character in the [[Book of Daniel]], a collection of legendary tales and visions dating from the 2nd century BC.{{sfn|Collins|2002|p=2}} The consensus among scholars is that [[Daniel (biblical figure)|Daniel]] never existed and was apparently chosen for the hero of the book because of his traditional reputation as a wise seer.{{sfn|Collins|1999|p=219}}{{sfn|Redditt|2008|p=180}} [[Daniel 1]] introduces Nebuchadnezzar as the king who takes Daniel and other Hebrew youths into captivity in Babylon, there to be trained in the magical arts. Through the help of God, Daniel excels in his studies, and the second year of Nebuchadnezzar's reign he interprets the king's dream of a huge image as God's prediction of the rise and fall of world powers, starting with Nebuchadnezzar's kingdom ([[Daniel 2]]). Nebuchadnezzar twice admits the power of the God of the Hebrews: first after [[Yahweh]] saves [[Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego|three of Daniel's companions]] from a fiery furnace ([[Daniel 3]]) and secondly after Nebuchadnezzar himself suffers a humiliating period of madness, as Daniel predicted ([[Daniel 4]]). | + | Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar is an important character in the [[Book of Daniel]] written in Chaldean language, a collection of legendary tales and visions dating from the 2nd century BC.{{sfn|Collins|2002|p=2}} The consensus among scholars is that [[Daniel (biblical figure)|Daniel]] never existed and was apparently chosen for the hero of the book because of his traditional reputation as a wise seer.{{sfn|Collins|1999|p=219}}{{sfn|Redditt|2008|p=180}} [[Daniel 1]] introduces Nebuchadnezzar as the Chaldean king who takes Daniel and other Hebrew youths into captivity in Babylon, there to be trained in the magical arts. Through the help of God, Daniel excels in his studies, and the second year of Nebuchadnezzar's reign he interprets the king's dream of a huge image as God's prediction of the rise and fall of world powers, starting with Nebuchadnezzar's kingdom ([[Daniel 2]]). Nebuchadnezzar twice admits the power of the God of the Hebrews: first after [[Yahweh]] saves [[Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego|three of Daniel's companions]] from a fiery furnace ([[Daniel 3]]) and secondly after Nebuchadnezzar himself suffers a humiliating period of madness, as Daniel predicted ([[Daniel 4]]). |

| − | The [[Book of Jeremiah]] contains a prophecy about Nebuchadnezzar as the " | + | The [[Book of Jeremiah]] contains a prophecy about Nebuchadnezzar as the "builder of nations" (Jer. 4:7) and gives an account of the [[siege of Jerusalem (587 BC)|siege of Jerusalem]] (587 BC) and the looting and destruction of the [[Solomon's Temple|First Temple]] (Jer. 39:1–10; 52:1–30). |

== Portrayal in medieval Muslim sources == | == Portrayal in medieval Muslim sources == | ||

| − | According to [[Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari]], Nebuchadnezzar, whose Persian name was Bukhtrashah, was of Persian descent, from the progeny of Jūdharz, however modern scholars are unanimous that he was either a native Mesopotamian ( | + | According to [[Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari]], Nebuchadnezzar, whose Persian name was Bukhtrashah, was of Persian descent, from the progeny of Jūdharz, however modern scholars are unanimous that he was either a native Mesopotamian ([[Babylonia]]n) or a [[Chaldea]]n. Some medieval writers erroneously believed he lived as long as 300 years.<ref name="Ṭabarī 1987 43–70">{{cite book|last=Ṭabarī|first=Muḥammad Ibn-Ǧarīr Aṭ-|title=The History of Al-Tabarī|year=1987|publisher=State Univ. of New York Pr.|pages=43–70}}</ref> While much of what is written about Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar depicts a great warrior, some texts describe a ruler who was concerned with both spiritual and moral issues in life and was seeking divine guidance.<ref>{{cite book|last=Wiseman|first=D.J.|title=Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon|year=1985|publisher=Oxford}}</ref> |

| − | Nebuchadnezzar was seen as a strong, conquering force in | + | Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar was seen as a strong, conquering force in Middle eastern texts and historical compilations, like [[Al-Tabari]]. The [[Babylon]]ian leader used force and destruction to grow an empire. He conquered kingdom after kingdom, including [[Phoenicia]], [[Philistia]], [[Kingdom of Judah|Judah]], [[Ammon]], [[Moab]], and more.<ref>{{cite book|last=Tabouis |first=G.R. |title=Nebuchadnezzar|year=1931|publisher=Whittlesey House|page=3}}</ref> The most notable events that Tabari’s collection focuses on is the [[Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC)|destruction of Jerusalem]].<ref name="Ṭabarī 1987 43–70" /> |

[[File:René-Antoine Houasse - Nabuchodonosor et Semiramis fait élever les jardins de Babylone (Versailles).jpg|thumb|center|upright=4.0|[[René-Antoine Houasse]]'s 1676 painting ''Nebuchadnezzar Ordering to your subjects the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to Please his Consort Amyitis'']] | [[File:René-Antoine Houasse - Nabuchodonosor et Semiramis fait élever les jardins de Babylone (Versailles).jpg|thumb|center|upright=4.0|[[René-Antoine Houasse]]'s 1676 painting ''Nebuchadnezzar Ordering to your subjects the construction of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to Please his Consort Amyitis'']] | ||

| Line 863: | Line 863: | ||

{{Commons category|Nebuchadnezzar II}} | {{Commons category|Nebuchadnezzar II}} | ||

{{AmCyc Poster|Nebuchadnezzar}} | {{AmCyc Poster|Nebuchadnezzar}} | ||

| − | * [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/10887 Inscription of Nabuchadnezzar. ''Babylonian | + | * [http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/10887 Inscription of Nabuchadnezzar. ''Babylonian Literature''] – old translation |

* [http://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/meso.html Nabuchadnezzar Ishtar gate Inscription] | * [http://www.kchanson.com/ANCDOCS/meso/meso.html Nabuchadnezzar Ishtar gate Inscription] | ||

* [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=154&letter=N&search=Nebuchadnezzar Jewish Encyclopedia on Nebuchadnezzar] | * [http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=154&letter=N&search=Nebuchadnezzar Jewish Encyclopedia on Nebuchadnezzar] | ||

Latest revision as of 10:43, 19 November 2023

| Nabû-kudurri-usur | |

|---|---|

| King of Babylon | |

An engraving with an inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II. Anton Nyström, 1901.[1] | |

| Reign | c. 605 – c. 562 BC |

| Predecessor | Nabopolassar |

| Successor | Amel-Marduk |

| Born | c. 634 BC |

| Died | c. 562 BC (aged 71–72) |

| Spouse | Amyitis |

| House | Chaldean |

| Father | Nabopolassar |

Nebuchadnezzar II (from Akkadian 𒀭𒀝𒆪𒁺𒌨𒊑𒋀 dNabû-kudurri-uṣur, Template:Hebrew and Chaldean Name), meaning "O god Nabu, preserve/defend my firstborn son") was king of Babylon c. 605 BC – c. 562 BC, the longest and most powerful reign of any monarch in the Neo-Babylonian empire.[2][3]

Contents

[hide]Career

Nebuchadnezzar was the eldest son and successor of Nabopolassar, a Chaldean official who rebelled and established himself as king of Babylon in 620 BC; the dynasty he established ruled until 539 BC, when the Neo-Babylonian Empire was conquered by Cyrus the Great.[4][5] Nebuchadnezzar is first mentioned in 607 BC, during the destruction of Babylon's arch-enemy of the cruel ancient Assyrian kings, at which point he was already crown Chaldean prince.[6] In 605 BC he and his ally Cyaxares, ruler of the Medes and Persians, led an army against the ancient Assyrians and Egyptians, who were then occupying Syria, and in the ensuing Battle of Carchemish, Necho II defeated them and Syria and Phoenicia were brought under the control of the Chaldean people of Mesopotamia.[7]

Nabopolassar died in August[citation needed] 605 BC, and Nebuchadnezzar returned to Babylon to ascend the throne.[8] For the next few years his attention was devoted to subduing his eastern and northern borders, and in 595/4 BC there was a serious but brief rebellion in Babylon itself.[9] In 594/3 BC the army was sent again to the west, possibly in reaction to the elevation of Psammetichus II to the throne of Egypt.[9] King Zedekiah of Judah attempted to organize opposition among the small states in the region, but his capital, Jerusalem, was taken in 587 BC (the events are described in the Bible's Books of Kings and Book of Jeremiah).[10] In the following years Nebuchadnezzar incorporated Phoenicia and the provinces of Cilicia (southwestern Anatolia) into his empire and may have campaigned in Egypt.[11] In his last years Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar, "pay[ing] no heed to son or daughter," and was deeply suspicious of his sons.[12] The kings who came after him ruled only briefly and Nabonidus, apparently not of the royal family, was overthrown by the Persian conqueror Cyrus the Great less than twenty-five years after Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar's death.

The ruins of Nebuchadnezzar's Babylon are spread over two thousand acres, forming the largest archaeological site in the Middle East.[13] He enlarged the royal palace (including in it a public museum, possibly the world's first), built and repaired temples, built a bridge over the Euphrates, and constructed a grand processional boulevard (the Processional Way) and gateway (the Ishtar Gate) lavishly decorated with glazed brick.[14] Each Spring equinox (the start of the New Year) the god Marduk would leave his city temple for a temple outside the walls, returning through the Ishtar Gate and down the Processional Way, paved with colored stone and lined with molded lions, amidst rejoicing crowds.[12]

Portrayal in the Bible

Chaldean King Nebuchadnezzar is an important character in the Book of Daniel written in Chaldean language, a collection of legendary tales and visions dating from the 2nd century BC.[15] The consensus among scholars is that Daniel never existed and was apparently chosen for the hero of the book because of his traditional reputation as a wise seer.[16][17] Daniel 1 introduces Nebuchadnezzar as the Chaldean king who takes Daniel and other Hebrew youths into captivity in Babylon, there to be trained in the magical arts. Through the help of God, Daniel excels in his studies, and the second year of Nebuchadnezzar's reign he interprets the king's dream of a huge image as God's prediction of the rise and fall of world powers, starting with Nebuchadnezzar's kingdom (Daniel 2). Nebuchadnezzar twice admits the power of the God of the Hebrews: first after Yahweh saves three of Daniel's companions from a fiery furnace (Daniel 3) and secondly after Nebuchadnezzar himself suffers a humiliating period of madness, as Daniel predicted (Daniel 4).

The Book of Jeremiah contains a prophecy about Nebuchadnezzar as the "builder of nations" (Jer. 4:7) and gives an account of the siege of Jerusalem (587 BC) and the looting and destruction of the First Temple (Jer. 39:1–10; 52:1–30).

Portrayal in medieval Muslim sources

According to Ali ibn Sahl Rabban al-Tabari, Nebuchadnezzar, whose Persian name was Bukhtrashah, was of Persian descent, from the progeny of Jūdharz, however modern scholars are unanimous that he was either a native Mesopotamian (Babylonian) or a Chaldean. Some medieval writers erroneously believed he lived as long as 300 years.[18] While much of what is written about Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar depicts a great warrior, some texts describe a ruler who was concerned with both spiritual and moral issues in life and was seeking divine guidance.[19]

Chaldean king Nebuchadnezzar was seen as a strong, conquering force in Middle eastern texts and historical compilations, like Al-Tabari. The Babylonian leader used force and destruction to grow an empire. He conquered kingdom after kingdom, including Phoenicia, Philistia, Judah, Ammon, Moab, and more.[20] The most notable events that Tabari’s collection focuses on is the destruction of Jerusalem.[18]

See also

References

Cite error: Invalid <references> tag;

parameter "group" is allowed only.

<references />, or <references group="..." />Bibliography

- Arnold, Bill T. (2005). Who Were the Babylonians?. BRILL. ISBN 9004130713.

- Bertman, Stephen (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518364-1.

- Cline, Eric H.; Graham, Mark W. (2011). Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88911-7.

- Dalley, Stephanie (1998). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814946-0.

- Foster, Benjamin Read; Foster, Karen Polinger (2009). Civilizations of Ancient Iraq. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-13722-6.

- Freedman, David Noel (2000). "Nebuchadnezzar". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Lee, Wayne E. (2011). Warfare and Culture in World History. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5278-4.

- Oates, J (1991). "The Fall of Assyria (635–609 BC)". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- Sweeney, Marvin A. (1996). Isaiah 1–39: With an Introduction to Prophetic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4100-1.

- Wiseman, D.J. (1991a). "Babylonia 605–539 BC". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22717-9.

- Wiseman, D.J. (1991b). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Lectures of The British Academy 1983. OUP/British Academy. ISBN 978-0-19-726100-2.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2008). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 0-495-39105-0.

- Bar, Shaul (2001). A letter that has not been read: dreams in the Hebrew Bible. Cincinnati: Hebrew Union College Press. ISBN 978-0-87820-424-3.

- Boyer, Paul S. (1992). When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-95129-8.

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2005). How To Read the Bible. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-1001-9.

- Carroll, John T. (2000). "Eschatology". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Cohn, Shaye J.D. (2006). From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-22743-2.

- Collins, John J. (1999). "Daniel". In Van Der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter Willem. Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2.

- Collins, John J. (1984). Daniel: With an Introduction to Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-0020-6.

- Collins, John J. (1993). Daniel. Fortress. ISBN 978-0-8006-6040-6.

- Collins, John J. (1998). The Apocalyptic Imagination: An Introduction to Jewish Apocalyptic Literature. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4371-5.

- Collins, John J. (2001). Seers, Sibyls, and Sages in Hellenistic-Roman Judaism. BRILL. ISBN 978-0-391-04110-3.

- Collins, John J. (2002). "Current Issues in the Study of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 9004116753.

- Collins, John J. (2003). "From Prophecy to Apocalypticism: The Expectation of the End". In McGinn, Bernard; Collins, John J.; Stein, Stephen J. The Continuum History of Apocalypticism. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-1520-2.

- Collins, John J. (2013). "Daniel". In Lieb, Michael; Mason, Emma; Roberts, Jonathan. The Oxford Handbook of the Reception History of the Bible. Oxford UNiversity Press. ISBN 978-0-19-164918-9.

- Crawford, Sidnie White (2000). "Apocalyptic". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Davies, Philip (2006). "Apocalyptic". In Rogerson, J. W.; Lieu, Judith M. The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford Handbooks Online. ISBN 978-0-19-925425-5.

- DeChant, Dell (2009). "Apocalyptic Communities". In Neusner, Jacob. World Religions in America: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-1-61164-047-2.

- Doukhan, Jacques (2000). Secrets of Daniel: Wisdom and Dreams of a Jewish Prince in Exile. Review and Herald Pub Assoc. ISBN 978-0-8280-1424-3.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2002). "The Danilic Son of Man in the New Testament". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 0-391-04128-2.

- Godden, Malcolm (2013). "Biblical Literature" The Old Testament". In Godden and, Malcolm; Lapidge, Michael. The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-46921-1.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002a). Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-46101-3.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2002b). "A Dan(iel) For All Seasons". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 9004116753.

- Grabbe, Lester L. (2010). An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism: History and Religion of the Jews in the Time of Nehemiah, the Maccabees, Hillel, and Jesus. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-55248-8.

- Hammer, Raymond (1976). The Book of Daniel. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-09765-9.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1999). Invitation to the Apocrypha. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-4633-4.

- Hill, Andrew E. (2009). "Daniel". In Garland, David E.; Longman, Tremper. Daniel—Malachi. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-59054-5.

- Hill, Charles E. (2000). "Antichrist". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Horsley, Richard A. (2007). Scribes, Visionaries, and the Politics of Second Temple Judea. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN 978-0-664-22991-7.

- Knibb, Michael (2002). "The Book of Daniel in its Context". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 9004116753.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2010). "Daniel". In Coogan, Michael D.; Brettler, Marc Z.; Newsom, Carol A. The new Oxford annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical books : New Revised Standard Version. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-937050-4.

- Lucas, Ernest C. (2005). "Daniel, Book of". In Vanhoozer, Kevin J.; Bartholomew, Craig G.; Treier, Daniel J. Dictionary for Theological Interpretation of the Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-2694-2.

- Matthews, Victor H.; Moyer, James C. (2012). The Old Testament: Text and Context. Baker Books. ISBN 978-0-8010-4835-7.

- McDonald, Lee Martin (2012). Formation of the Bible: the Story of the Church's Canon. Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-59856-838-7. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Miller, Steven R. (1994). Daniel. B&H Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8054-0118-9.

- Niskanen, Paul (2004). The Human and the Divine in History: Herodotus and the Book of Daniel. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-08213-8.

- Provan, Iain (2003). "Daniel". In Dunn, James D. G.; Rogerson, John William. Eerdmans Commentary on the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-3711-0.

- Redditt, Paul L. (2009). Introduction to the Prophets. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2896-5.

- Reid, Stephen Breck (2000). "Daniel, Book of". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Rowland, Christopher (2007). "Apocalyptic Literature". In Hass, Andrew; Jasper, David; Jay, Elisabeth. The Oxford Handbook of English Literature and Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927197-9.

- Ryken,, Leland; Wilhoit, Jim; Longman, Tremper (1998). Dictionary of Biblical Imagery. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-6733-2.

- Sacchi, Paolo (2004). The History of the Second Temple Period. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-567-04450-1.

- Schwartz, Daniel R. (1992). Studies in the Jewish Background of Christianity. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3-16-145798-2.

- Seow, C.L. (2003). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-25675-3.

- Schiffman, Lawrence H. (1991). From Text to Tradition: A History of Second Temple and Rabbinic Judaism. KTAV Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-88125-372-6.

- Spencer, Richard A. (2002). "Additions to Daniel". In Mills, Watson E.; Wilson, Richard F. The Deuterocanonicals/Apocrypha. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-510-6.

- Towner, W. Sibley (1984). Daniel. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 978-0-664-23756-1.

- VanderKam, James C. (2010). The Dead Sea Scrolls Today. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-6435-2.

- VanderKam, James C.; Flint, Peter (2013). The meaning of the Dead Sea scrolls: their significance for understanding the Bible, Judaism, Jesus, and Christianity. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-224330-0.

- Waters, Matt (2014). Ancient Persia: A Concise History of the Achaemenid Empire, 550–330 BC. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-65272-9.

- Weber, Timothy P. (2007). "Millennialism". In Walls, Jerry L. The Oxford Handbook of Eschatology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974248-6.

- Wesselius, Jan-Wim (2002). "The Writing of Daniel". In Collins, John J.; Flint, Peter W.; VanEpps, Cameron. The Book of Daniel: Composition and Reception. BRILL. ISBN 0-391-04128-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nebuchadnezzar II. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Nebuchadnezzar. |

- Inscription of Nabuchadnezzar. Babylonian Literature – old translation

- Nabuchadnezzar Ishtar gate Inscription

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Nebuchadnezzar

- Nebuchadnezzar II on Ancient History Encyclopedia

| Preceded by Nabopolassar |

King of Babylon 605 BC – 562 BC |

Succeeded by Amel-Marduk |

- Jump up ↑ Anton Nyström, Allmän kulturhistoria eller det mänskliga lifvet i dess utveckling, bd 2 (1901)

- Jump up ↑ Freedman 2000, p. 953.

- Jump up ↑ "Nebuchadnezzar II". ancient.eu. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- Jump up ↑ Bertman 2005, p. 95.

- Jump up ↑ Oates 1997, p. 162.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman 1991a, p. 182.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman 1991a, p. 182–183.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman 1991a, p. 183.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 Wiseman 1991a, p. 233.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman 1991a, p. 233–234.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman 1991a, p. 235–236.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Foster 2009, p. 131.

- Jump up ↑ Arnold 2005, p. 96.

- Jump up ↑ Bertman 2005, p. 96.

- Jump up ↑ Collins 2002, p. 2.

- Jump up ↑ Collins 1999, p. 219.

- Jump up ↑ Redditt 2008, p. 180.

- ↑ Jump up to: 18.0 18.1 Ṭabarī, Muḥammad Ibn-Ǧarīr Aṭ- (1987). The History of Al-Tabarī. State Univ. of New York Pr. pp. 43–70.

- Jump up ↑ Wiseman, D.J. (1985). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon. Oxford.

- Jump up ↑ Tabouis, G.R. (1931). Nebuchadnezzar. Whittlesey House. p. 3.

- Pages with script errors

- All articles with unsourced statements

- Articles with unsourced statements from March 2018

- Articles with invalid date parameter in template

- Commons category with local link different than on Wikidata

- 630s BC births

- 560s BC deaths

- 6th-century BC biblical rulers

- 7th-century BC biblical rulers

- Babylonian kings

- Book of Daniel

- Babylonian captivity

- Nebuchadnezzar II

- Monarchs of the Hebrew Bible

- Chaldean kings

- Angelic visionaries