Sennacherib

| Sennacherib | |

|---|---|

|

King of Assyria, Babylonia, Akkad and Sumer ܡܠܟܐ ܕܐܬܘܪ ܘܒܒܠ ܘܐܟܕ ܘܫܘܡܪ Malkā d-ʾĀṯūr w-Bāḇēl w-Akkad w-Šūmēr | |

Sennacherib during his Babylonian war, relief from his palace in Nineveh | |

| Reign | 705–681 BCE |

| Predecessor | Sargon II |

| Successor | Esarhaddon |

| Born |

c. 740 BC Kalhu |

| Died |

681 BCE Nineveh |

| Spouse |

Tašmētu-šarrat Naqī'ā/Zakūtu |

| Issue |

Aššur-nādin-šumi Aššur-ilī-muballissu Arda-Mulišši (Adrammelech) Aššur-šumu-ušabši Nergal-MU-... Nabu-šarru-uṣur (Sharezer) Aššur-aḥa-iddina (Esarhaddon) |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Sargon II |

| Mother | Ra'īmā |

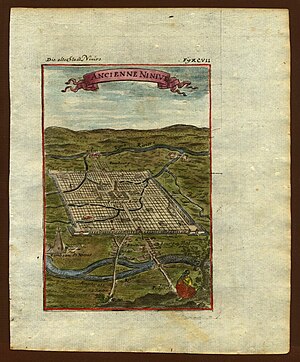

Sennacherib (Akkadian: Sîn-ahhī-erība, "Sîn has replaced the brothers"; Syriac: ܣܝܢܚܪܝܒ; Template:Hebrew Name[1] pronounced in Modern Hebrew Template:IPA-he or in some Mizrahi dialects Template:IPA-he) was the king of Assyria from 705 BCE to 681 BCE. He is principally remembered for his military campaigns against Babylon and Judah, and for his building programs – most notably at the Akkadian capital of Nineveh.[2] He was assassinated in obscure circumstances in 681 BCE,[3] apparently by his eldest son (his designated successor, Esarhaddon, was the youngest).[4]

The primary preoccupation of his reign was the so-called "Babylonian problem", the refusal of the Babylonians to accept Assyrian rule, culminating in his destruction of the city in 689 BCE.[5] Further campaigns were carried out in Syria (notable for being recorded in the Bible's Books of Kings[6]) in the mountains east of Assyria, against the kingdoms of Anatolia and against the Arabs in the northern Arabian deserts.[7] His death was welcomed in Babylon as divine punishment for the destruction of that city.[8]

He was also a notable builder: it was under him that Assyrian art reached its peak.[9] His building projects included the beautification of Nineveh, a canal 50 km long to bring water to the city,[10] and the "Palace Without Rival", which included what may have been the prototype of the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon, or even the actual Hanging Gardens.[11]

Contents

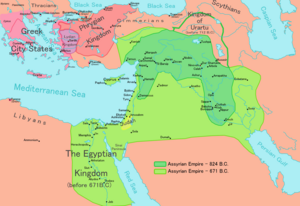

Background: The Neo-Assyrian empire, 911–612 BCE

Assyria began as a Bronze Age city-state or small kingdom on the middle-Tigris.[12] The kingdom collapsed at the end of the Bronze Age, but was reconstituted at the beginning of the Iron Age, and under Tiglath-pileser III and his sons Shalmaneser V and Sargon II (combined reigns 744–705 BCE), Assyria extended its rule over Mesopotamia, Anatolia and Syria-Palestine, making its capital Nineveh, one of the richest cities of the ancient world.[13][14] The empire's rise aroused the fear and hatred of its neighbours, notably Babylon, Elam and Egypt, and the many smaller kingdoms of the region such as Judah. Any perceived weakness on the part of Assyria led inevitably to rebellion, particularly by the Babylonians.[15] Solving the so-called "Babylonian problem" was Sennacherib's primary preoccupation.[16]

The "Babylonian problem"

Sennacherib's grandfather Tiglath-pileser III had made himself king of Babylon, creating a dual monarchy in which the Babylonians retained a nominal independence. This arrangement was never accepted by powerful local leaders, particularly an important tribal chief named Marduk-apla-iddina (the Merodach-baladan of the Bible). Marduk-apla-iddina paid tribute to Tiglath-pileser, but when Tiglath-pileser's successor Shalmaneser V was overthrown by Sargon II (Sennacherib's father) he seized the opportunity to crown himself king of Babylon. The next thirty years saw a repeating pattern of Assyrian reconquest and renewed rebellion.[17]

Sargon dealt with the Babylonian problem by cultivating the Babylonians; Sennacherib took a radically different approach, and there is little sign that he cared about Babylonian popular opinion or took part in the ceremonial duties expected of a Babylonian king, notably the New Year ritual. His relations, instead, were predominantly military, and culminated in his complete destruction of Babylon in 689 BCE.[18] He destroyed the temples and the images of the gods, except for that of Marduk, the creator-god and divine patron of Babylon, which he took to Assyria.[19] This caused consternation in Assyria itself, where Babylon and its gods were held in high esteem.[20] Sennacherib attempted to justify his actions to his own countrymen through a campaign of religious propaganda.[21] Among the elements of this campaign he commissioned a myth in which Marduk was put on trial before Ashur, the god of Assyria–the text is fragmentary but it seems Marduk is found guilty of some grave offense;[22] he described his defeat of the Babylonian rebels in language of the Babylonian creation myth, identifying Babylon with the evil demon-goddess Tiamat and himself with Marduk;[23] Ashur replaced Marduk in the New Year Festival; and in the temple of the festival he placed a symbolic pile of rubble from Babylon.[24] In Babylon itself, Sennacherib's answer to the Babylonian problem sparked an intense hatred that would eventually lead to a war for independence and the destruction of Assyria.[25]

Accession and military campaigns

Accession

Sennacherib was probably not the first-born son of Sargon II (his name implies a compensation for dead brothers), but he was groomed for royal succession and entrusted with administrative duties from an early age.[26] Sargon died in battle, and ancient sources give three different years for Sennacherib's first reign-year—705 BCE, 704 BCE, and 703 BCE—suggesting that the succession was not smooth.[16] The transition sparked uprisings in Syria-Palestine, where the Egyptians incited rebellion, and more seriously in Babylon, where Marduk-apla-iddina II assumed the throne and assembled a large army of Chaldeans, Aramaeans, Arabs and Elamites.[26]

Military campaigns in Mesopotamia, Syria, Israel, and Judah

Template:Infobox military conflict Sennacherib's first campaign began late in 703 BCE against Marduk-apla-iddina (now Marduk-apla-iddina II), who had once more taken the throne of Babylon.[27] The rebellion was defeated, Marduk-apla-iddina fled, and Babylon was taken and the palace plundered, although the citizens were not harmed.[27] A puppet king named Bel-ibni was placed on the throne and for the next two years Babylon was left in peace.[27]

In 701 BCE, Sennacherib turned from Babylonia to the western part of the empire, where Hezekiah of Judah, incited by Egypt and Marduk-apla-iddina, had renounced Assyrian allegiance. The rebellion involved various small states in the area: Sidon and Ashkelon were taken by force and a string of other cities and states, including Byblos, Ashdod, Ammon, Moab and Edom then paid tribute without resistance. Ekron called on Egypt for help but the Egyptians were defeated. Sennacherib then turned on Jerusalem, Hezekiah's capital. He besieged the city and gave its surrounding towns to Assyrian vassal rulers in Ekron, Gaza and Ashdod. Sennacherib however never breached the city.[28] The Bible states that an angel of the Lord killed 185,000 Assyrian troops, ending the siege on Jerusalem.[29] Hezekiah remained on his throne as a vassal ruler.[30] The campaign is recorded with differences in the Assyrian records and the biblical Books of Kings.

In 699 BCE, Bel-ibni, who had proved untrustworthy or incompetent as king of Babylon, was replaced by Sennacherib's eldest son, Ashur-nadin-shumi.[31] Marduk-apla-iddina continued his rebellion with the help of Elam, and in 694 Sennacherib took a fleet of Phoenician ships down the Tigris River to destroy the Elamite base on the shore of the Persian Gulf, but while he was doing this the Elamites captured Ashur-nadin-shumi and put Nergal-ushezib, the son of Marduk-apla-iddina, on the throne of Babylon.[20] Nergal-ushezib was captured in 693 BCE and taken to Nineveh, and Sennacherib attacked Elam again. The Elamite king fled to the mountains and Sennacherib plundered his kingdom, but when he withdrew the Elamites returned to Babylon and put another rebel leader, Mushezib-Marduk, on the Babylonian throne. Babylon eventually fell to the Assyrians in 689 BCE after a lengthy siege, and Sennacherib put an end to the "Babylonian problem" by utterly destroying the city and even the mound on which it stood by diverting the water of the surrounding canals over the site.[25] (In fact the problem had not been solved: in 612 BCE a coalition of Babylonians and other enemies of Assyria sacked Nineveh, marking the end of the Assyrian empire).[32]

Minor campaigns

Sennacherib conducted minor campaigns on his borders, but without significantly adding to the empire. In 702 BCE and from 699 BCE until 697 BCE, he made several campaigns in the mountains east of Assyria, on one of which he received tribute from the Medes. In 696 BCE and 695 BCE, he sent expeditions into Anatolia, where several vassals had rebelled following the death of Sargon. Around 690 BCE, he campaigned in the northern Arabian deserts, conquering Dumat al-Jandal, where the queen of the Arabs had taken refuge.[33]

Administration and building projects

The Assyrian empire was divided into provinces, each provincial governor being responsible for matters such as the maintenance of roads and public buildings, and for the implementation of administrative policy. One major element of that policy was the massive deportation and redistribution of populations, which aimed to punish, prevent rebellion, and repopulate depopulated areas in order to maintain food production in the empire. As many as 4.5 million people may have been moved between 745 BCE and 612 BCE, and Sennacherib alone could have been responsible for displacing 470,000 people.[34]

Sennacherib made Nineveh a truly magnificent city. He laid out new streets and squares and built within it the famous "palace without a rival", the plan of which has been mostly recovered and has overall dimensions of about 503 by 242 metres (1,650 by 794 ft). It comprised at least 80 rooms, many of which were lined with sculpture. A large number of cuneiform tablets were found in the palace. The solid foundation was made out of limestone blocks and mud bricks; it was 22 metres (72 feet) tall. In total, the foundation is made of roughly 2,680,000 cubic metres (3,510,000 cubic yards) of brick (approximately 160 million bricks). The walls on top, made out of mud brick, were an additional 20 metres (66 feet) tall. Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone door figures weighing up to 30,000 kilograms (30 t); they included many winged lions or bulls with a man's head. These were transported 50 kilometres (31 miles) from quarries at Balatai and they had to be lifted up 20 metres (66 feet) once they arrived at the site, presumably by a ramp. There are also 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) of stone panels carved in bas-relief, that include pictorial records documenting every construction step including carving the statues and transporting them on a barge. One picture shows 44 men towing a colossal statue. The carving shows three men directing the operation while standing on the Colossus. Once the statues arrived at their destination, the final carving was done. Most of the statues weigh between 9,000 and 27,000 kg (20,000 and 60,000 lb).[9][10]

The stone carvings in the walls include many battle scenes, impalings and scenes showing Sennacherib's men parading the spoils of war before him. He also bragged about his conquests: he wrote of Babylon: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." He later wrote about a battle in Lachish: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke...him I shut up in Jerusalem his royal city like a caged bird. Earthworks I threw up against him, and anyone coming out of his city gate I made pay for his crime. His cities which I had plundered I had cut off from his land." [11]

At this time, the total area of Nineveh comprised about 7 square kilometres (1,700 acres), and fifteen great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently constructed aqueduct erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, about 65 kilometres (40 miles) distant. [12] The enclosed area had more than 100,000 inhabitants (maybe closer to 150,000), about twice as many as Babylon at the time, placing it among the largest settlements worldwide.

It is possible that the garden which Sennacherib built next to his palace, with its associated irrigation works, was the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon.[35]

Death

Sennacherib was assassinated in obscure circumstances in 681 BCE.[3] An inscription by Sennacherib's successor, Esarhaddon, describes how Esarhaddon heard that his brothers were fighting in the streets of Nineveh, hurried back from the Western provinces with an army, defeated them all, and took the throne.[36] The inscription does not mention that the brothers were fighting because one of them had just murdered Sennacherib, but this is indicated in the Babylonian chronicles, the Bible (Isaiah 37:36–38, Tobit 1:21), and in later Assyrian records.[36][4] Esarhaddon's silence on the subject of the name of his father's murderer may have been to avoid perpetuating any perceptions of instability.[37] To one Babylonian historian, it was divine punishment for what the king had done to Babylon.[8]

Professor Simo Parpola, basing his findings on a fragmented letter surviving from that period,[38] holds that Arda-Mulišši, known as Adrammelech in the Bible, was the son who killed the King, and that a series of events beginning in 694 BCE set the stage for the assassinaton.[39] In 694, Sennacherib's oldest son and heir-designate Assur-nãdin-sumi was captured by Babylonians and was removed to Elam, whereafter he disappears from the historical record. Arda-Mulišši, the next eldest son, was expected to be the next heir-designate. However, Naqi'a Zakitu, the king's second wife, (entirely unrelated to Arda-Mulišši) used her influence to have the King proclaim her own sickly and frail son Esarhaddon the heir-designate. Sennacherib made all of Assyria swear allegiance to the new crown prince.

Despite this, Arda-Mulišši continued to be a popular figure among the powerful at court. Over the following years, dislike of Esarhaddon grew in court, and simultaneously the popularity of Arda-Mulišši and his other brothers expanded. Worried over this turn of events, Sennacherib sent Crown Prince Esarhaddon to the safety of the western provinces. Arda-Mulišši, feeling that a decisive act would grant him the kingship, made "a treaty of rebellion" with co-conspirators and moved to kill his father. Sennacherib was then murdered, either by being stabbed directly by his son, or by being crushed as he prayed underneath a statue of a winged bull colossus that guarded the temple.[39]

See also

- Ahikar, Sennacherib's chancellor

- Rabshakeh, Sennacherib's cupbearer

- Assyrian siege of Jerusalem

- The Destruction of Sennacherib

References

Cite error: Invalid <references> tag;

parameter "group" is allowed only.

<references />, or <references group="..." />Bibliography

- Bertman, Stephen (2005). Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Brinkman, J.A. (1991). "Babylonia in the Shadow of Assyria (747-626 B.C.)". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press.

- Cline, Eric H.; Graham, Mark W. (2011). Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam. Cambridge University Press.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: An Elusive World Wonder Traced. Oxford University Press.

- Dalley, Stephanie (1998). The Legacy of Mesopotamia. Oxford University Press.

- Foster, Benjamin Read; Foster, Karen Polinger (2009). Civilizations of Ancient Iraq. Princeton University Press.

- Grabbe, Lester (2003). Like a Bird in a Cage: The Invasion of Sennacherib in 701 BCE. A&C Black.

- Grayson, A.K. (1991). "Assyria: Sennacherib and Essarhaddon". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2009). Historical Dictionary of Mesopotamia. Scarecrow Press.

- McCormack, Clifford Mark (2002). Palace and Temple. Walter de Gruyter.

- McKenzie, John L. (1995). The Dictionary Of The Bible. Simon and Schuster.

- Oates, Joan (1991). "The Fall of Assyria (635–609 BCE)". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S. The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III Part II. Cambridge University Press.

- Porter, Barbara Nevling (1994). Images, Power, and Politics. American Philosophical Society.

- Russell, John Malcolm (1991). Sennacherib's "Palace Without Rival" at Nineveh. University of Chicago Press.

- Von Soden, Wolfram (1994). The Ancient Orient: An Introduction to the Study of the Ancient Near East. Eerdmans.

External links

- [1] Daniel David Luckenbill, The Annals of Sennacherib, Oriental Institute Publications 2, University of Chicago Press, 1924

- Rare Stela of Sennacherib.

- Prism of Sennacherib

- The murderer of Sennacherib – by Simo Parpola

- Sennacherib's Invasion of Judah – by Craig C. Broyles

- Interactive Map of Sennacherib's Invasion of Judah, including the accounts of Sennacherib, Herodotus, 2 Kings, Isaiah and Micah

- States that the prism is preserved in the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

- A site on the study of King Sennacherib by Jack Taylor, II

- First Campaign of Sennacherib Translated Cylinder 113203. British Museum

| Preceded by Sargon II |

King of Babylon 705 – 703 BCE |

Succeeded by Marduk-zakir-shumi II |

| King of Assyria 705 – 681 BCE |

Succeeded by Esarhaddon | |

| Preceded by Mušezib-Marduk |

King of Babylon 689–681 BCE |

Succeeded by Esarhaddon |

- ↑ As seen in 2Kings 18:13, Isaiah 36:1, Isaiah 37:17, and 2Chronicles 32:1

- ↑ McKenzie 1995, p. 786.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cline & Graham 2011, p. 252.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Grayson 1991, p. 121.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 105,109.

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 308–309.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 111–113.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Foster & Foster 2009, p. 123.

- ↑ Von Solden 1994, p. 58.

- ↑ Von Solden 1994, p. 58,100.

- ↑ Foster & Foster 2009, p. 121-123.

- ↑ Cline & Graham 2011, p. 37.

- ↑ Bertman 2005, p. 57.

- ↑ Cline & Graham 2011, p. 40.

- ↑ Bertman 2005, p. 40.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Grayson 1991, p. 105.

- ↑ Brinkman 1991, p. 24-32.

- ↑ Brinkman 1991, p. 32-37.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 118.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Leick 2009, p. 156.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 118-119.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 119.

- ↑ McCormick 2002, p. 156,158.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 116.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Grayson 1991, p. 109.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Leick 2009, p. 155.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Grayson 1991, p. 106.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 110.

- ↑ 2 Kings 19:35

- ↑ Grabbe 2003, p. 314.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 107-108.

- ↑ Oates 1991, p. 180.

- ↑ Grayson 1991, p. 111-113.

- ↑ Cline & Graham 2011, p. 50.

- ↑ Stephanie Dalley (2013)The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive world Wonder traced OUP ISBN 978-0-19-966226-5

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Porter 1994, p. 108.

- ↑ Porter 1994, p. 108-109.

- ↑ Assyrian and Babylonian Letters XI, No.1091. Originally translated by R. Harper. Chicago 1911.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Simo Parpola (1980). "The Murderer of Sennacherib". Gateways to Babylon.